|

and flood protection and healthy waterways for California's communities, economy and environment. That's the goal and the promise of our newest state initiative.

This week Governor Gavin Newsom directed California's water agencies to prepare a resilient water portfolio that will meet California's needs for the 21st century. You can read the order by clicking here. One thing I really appreciate about this new order is that Newsom acknowledges that water infrastructure can and should include natural elements of our landscape, including forests and floodplains. He also calls for some effective strategies in developing our water portfolio of the future, including working regionally at the watershed level and incorporating successful strategies from different parts of the world. Looking back at the history of western civilization in California, it's easy to see that we have done none of those things in the past 150 years. Our water strategy is directly descended from the Gold Rush mining practices that started with gold panning, progressed to sluicing and then quickly leveraged new technologies to develop hydraulic mining. That particular technological innovation ended up devastating river after river by dumping epic amounts of sediment and gravel that forever changed the way that water flows down from the mountains in the east, through the Central Valley and out through the San Francisco Bay. Hydraulic mining poisoned our fisheries with mercury and arsenic and forever stopped the riverboats from being able to navigate the Sacramento River to Marysville. The Gold Rush is also responsible for our love of hydropower and dams, as our very first electrical grid in California came from hydroelectric plants and dams on the Yuba River. The Stairway of Power on the North Fork of the Feather River created a series of dams that eventually culminated in the Oroville Dam and Hyatt Power Plant. All that low-carbon and climate-friendly energy has powered homes and industries for many years, but it's also raised very serious questions about how we'll be managing these dams and reservoirs into the next century as they continue to fill with sediment and age well past their design lifetimes. Flood control from dams and levees have carved out great sections of land in the Central Valley that have become productive farmland and made our farming families wealthy, and water is moved great distances to the enormous cities of Southern California. But we should always ask ourselves who is benefitting from this enormous water infrastructure and who is paying the cost? When the dam spillway fails, it's the rural residents living downstream who are at risk. So when Newsom directs our state agencies to embrace new technologies and innovation, I add that we need to be very cautious in evaluating these new options. All too often, we fall in love with technology and forget about how we're paying for it, whether it's our fisheries, our navigable rivers, or our clean, drinkable water. My first recommendation is to analyze what elements of a new technology are being externalized - who or what will have to live with the byproducts or labor or degraded environment? I've been falling in love with simpler technologies that are associated with smaller infrastructure projects distributed more widely across the land, so that when a failure occurs it is not catastrophic. I'm falling in love with projects that incorporate ecological systems from the very beginning of the design process. I'm already committed to doing more than plan and build water infrastructure but commit to generations of monitoring and assessment of projects so that we can learn from them, study projects in a changing climate, and make adjustments and improvements as we go along. Ask anyone who lives in Oroville: a dam is not a static, motionless monument but is a dynamic system in motion that requires huge commitments of time and money to maintaining and monitoring.

2 Comments

I often speak at public meetings about the state of affordable housing in our region. In both our rural and larger towns, we’re seeing many of the same challenges as large urban areas:

What is the federal role in affordable housing, and how can we make improvements? The federal government has a housing subsidy program, called Section 8, that provides housing vouchers that can be associated with a renter or with a particular housing unit. In our region of California, like many other places, the program is not working very well. There are also federal financial incentive programs to encourage development of affordable housing, but in many rural areas, we are not seeing any new housing development, much less affordable housing development, so these programs do not have much impact on our communities. In the end, much of our less-expensive housing units are old, dilapidated, and may contain hazardous building materials or mold that is not healthy for tenants. I think we can develop innovative programs that can help coordinate federal, state, and local programs and laws to improve affordable housing.

This week I spent several days with representatives from the Maidu community, government agencies, non-profits, and academia in Genesee Valley, Plumas County. We camped in a beautiful stand of trees during the hottest day of the year and got drenched in a thunderstorm and talked and laughed and learned together. It was an honor to be invited to participate in this gathering. I learned so much that it’s hard to capture in a short article.

We talked and talked and talked about future projects that balance fire resistance with timber production and ecosystem restoration. These kinds of meetings are critical to California’s future, and we need to talk a lot more about how to best model the way and scale up projects to cover our entire forest landscape. For more information about Genesee Valley and forest planning, visit these websites: http://www.geneseefireplan.org/news.html http://www.plumasaudubon.org/genesee-valley.html http://www.frlt.org/conserve-land/success-stories/heart-k-ranch Since I’ve had a chance to live and spend time in Japan, the United States, and Mexico, not to mention all the time spent in industrial facilities all over the world, I’ve been able to see a number of different approaches to razing buildings. I love the term “razing,” because it can encompass a whole range of different techniques.

The most elegant work I’ve seen is in Tokyo, where space constraints and very strict waste management rules means that buildings are not demolished but are dismantled piece by piece. Here is a great little video that shows some of the challenges and solutions of working in Japan. I’ve inspected many recycling facilities and building sites in Japan, and I will forever be in awe at the degree to which waste materials are separated and recycled, to avoid creating waste that must go into scarce landfill space. We could all learn a lot about recycling from Japan. There is even one technique, Daruma Otoshi, that involves removing a floor at a time, starting at the bottom of the building. This remains one of my favorite ever demolition videos, especially since I’ve spent a lot of time inside the Prince Hotel before it was closed down. And another short video that does a great job of showing Daruma Otoshi in time lapse. With our excess of space and cheap landfills in the United States, we’re not quite so careful. In fact, we’re famous for our method of imploding buildings, which has spread to other areas of the world. There are even highlight reels of annual building implosions, including this one. Of course, we still demolish most buildings with heavy equipment and a lot of time and effort. Two of the most common methods are with a wrecking ball (old school) and with a high reach excavator (newer school). Building demolition in the U.S. can create a huge amount of dust, and cleaning up afterwards is really just picking everything up and trucking it all to a landfill. That means you have to remove any hazardous building materials before any demolition starts. Hazardous building materials can include asbestos, both in insulation and in everything from wall board to floor tiles. Use of friable asbestos was phased out before 1980, but asbestos can still be found in a wide range of building materials at relatively low concentrations. Lead-based paint has a similar story. It is still used on some exterior applications and was used quite a bit on interiors before 1978. Before polychlorinated biphenyls were banned in 1979, they were used extensively as insulation in liquid filled electrical equipment ranging from transformers and capacitors to small fluorescent light fixture ballasts. PCBs were also used as a plasticizer in paint (mostly in places like ships), and caulking. All of these hazardous building materials are strictly regulated as wastes and must be separated from other kinds of demolition waste. Asbestos gets landfilled in specially designed landfills where it can be sufficiently contained. Lead debris gets stabilized by mixing with concrete so that it won’t leach into the groundwater when it is landfilled. And all PCB waste gets incinerated at facilities that are designed to destroy these persistent organic chemicals at a 99.9999% destruction and removal efficiency. I am often asked about why cleanup activities in California are more complicated than in other states. The quick answer is that California has several different laws that could trigger cleanups, and there may be a number of different regulatory agencies involved depending on the source of the contamination and the extent of contamination - whether soil, groundwater, surface water, or sediment is affected.

California is like other states, in that you must identify all the exposure pathways and address risks for human health and environmental receptors in order to close out a hazardous substance or petroleum release site. Background levels for metals can be used to support a finding of no release. Each agency has its own closeout checklist that is completed as part of the final assessment prior to regulatory closure. Engineering controls and institutional controls are used to supplement cleanup remedies and may remain in place in perpetuity through deed notices and deed restrictions. The process for completing remediation varies from one regulatory program to another. The key regulatory programs include:

DTSC uses soil cleanup standards that are geared toward human exposure and are developed by the Office of Environmental Health Hazard Assessment (OEHHA): http://www.oehha.org/risk.html DTSC also has its own method for assessing risks from soil vapor intrusion: https://dtsc.ca.gov/SiteCleanup/Vapor_Intrusion.cfm The SWRCB is a state agency, with Regional Water Quality Control Boards (RWQCBs) for nine regions across California. Water protection, for groundwater and surface waters, fall under the authority of these agencies. Environmental Screening Levels (ESL) were established for a wide range of exposure pathways and environmental conditions, and they address both human and environmental receptors. These are updated quite frequently, most recently in 2013. The Los Angeles and San Francisco Bay regional boards put these together, but they are applied across the state. http://www.waterboards.ca.gov/rwqcb2/water_issues/programs/esl.shtml In order to properly apply the ESLs, it’s critical that the applicable basin plan be consulted to identify all beneficial uses of surface and groundwater for the subject site, as these beneficial uses will drive the selection of screening criteria. For complex sites where screening levels may not adequately address multiple contaminants or synergistic effects, USEPA’s CERCLA risk assessment methodology may be used to set cleanup levels for a cleanup project. In Arizona, there are three regulatory paths for stormwater discharge at industrial facilities:

This program falls under the National Pollutant Discharge Elimination System (NPDES) stormwater program of the national Clean Water Act, as applicable to the state and local jurisdiction where the subject property is located. States adopt general permits that cover a wide range of industrial and business activities. A permit must be obtained for facilities where stormwater is considered “contact stormwater”, from either the state or the city, depending on where the stormwater is discharged. However, some industrial activities are not covered or exempted under general permit standards. Non-contact stormwater flows on an industrial property means stormwater that does not come into contact with industrial operations or loading/unloading activities. For facilities that are not planning discharge pollutants into the stormwater system, there are two ways to proceed:

Our children will enjoy in their homes electrical energy too cheap to meter... It is not too much to expect that our children will know of great periodic regional famines in the world only as matters of history, will travel effortlessly over the seas and under them and through the air with a minimum of danger and at great speeds, and will experience a lifespan far longer than ours, as disease yields and man comes to understand what causes him to age.

Lewis Strauss, chair of the Atomic Energy Commission Even if you build the perfect reactor, you're still saddled with a people problem and an equipment problem. David R. Brower, environmental activist and founder of the Sierra Club I just started following The National Interest’s blog, and I’m enjoying the international perspective and diversity of contributors. I’m always interested in alternatives to carbon-based energy, and recently John Quiggin, an Australian economist, wrote about why he thinks that China’s nuclear program could work for them (Link: http://nationalinterest.org/commentary/china-can-make-nuclear-power-work-9815). I grew up in a time when nuclear power was going to solve all our energy problems, making electricity too cheap to meter. But Quiggin points out that even by the time the Three Mile Island meltdown occurred 1979, the nuclear plant building boom in the United States was nearing an end. Long delays, cost overruns, and public opposition resulted in no new nuclear plants being completed after 1980. In contrast, the French were successful at building a large number of nuclear reactors, in an effort to convert completely to nuclear energy in the wake of the 1970s energy crises. Arnulf Grubler, one of my favorite professors at Yale, pointed to four key factors in the success of the French:

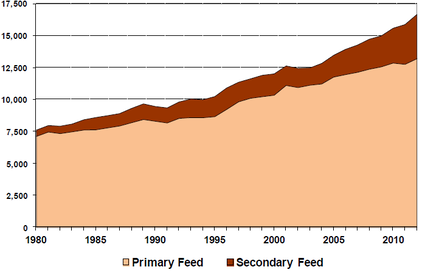

Could China, which seems to have a lot in common with 1970s France, make nuclear power work for them to reduce the amount of coal they are burning? Quiggin seems to think it’s a good possibility and would be beneficial for everyone on our planet. He points out that “China is ruled by a modernising elite that’s procapitalist but happy to exercise state control over the economy, and to ignore or crush public opposition. Like France, China seems likely to standardize on a single Westinghouse model, the AP1000. So, it’s unsurprising to see Chinese nuclear projects being completed on time and on budget while similar projects in the US and Europe are floundering.” Of course, it might be difficult for those conditions to be sustained in China into the future, and if renewables become economically competitive, nuclear could be less attractive. I’ve spent a lot of time at all kinds of factories in China, including a number of coal fired power plants, biowaste facilities, and co-generation plants at large industrial plants. I’ve audited solar panel fabrication plants, transformer factories, and all kinds of factories making manufactured goods like CAT scan machines, escalators, and refrigerators. What worries me about nuclear power in China are the two things I see in common with all these facilities: not one of them had bothered going through the effort to get all their environmental permits in place, and not one of them had an appropriate operations and maintenance program to ensure that conditions at the factory when it was built would be sustained for more than a year or two after completion. And that brings me back to David Brower’s quote. Given the complexity and inherent risks associated with nuclear power, its success rests on the people and their ability to understand and maintain the equipment they are working with. I’m not sure any government or company can manage that for nuclear power over the lifetime of the plant and the waste it produces.  I’m starting to work on several projects involving the demolition of industrial buildings in city neighborhoods to make way for residential redevelopment. It’s really interesting to see neighborhoods slowly transform from sleepy, gray streets with monolithic, windowless buildings into jumbles of apartment buildings and stores and trees and parking lots, and then to see those areas fill up with people over a period of just a few years. There’s a lot of work that goes into turning an industrial property into land that’s suitable for families and children. I thought it would be fun to write a series of blog posts about what happens when an industrial facility is demolished, and later I’ll write about what happens below ground with the soil and groundwater. Copper is probably the most valuable item left in a factory once it’s been shut down. According to the international copper association (2012 World of Copper Factbook), 32% of all copper produced is used in building construction, and another 14% is used in infrastructure like our electrical grid. The remainder is used in equipment, and these days a large amount of copper ends up on printed circuit boards and wiring that goes into our consumer electronics. One of my former professors at Yale, Thomas Graedel, has spent the last few decades tracking down how copper is used through its entire lifecycle, and he estimates that 156 kg of copper is used to support the modern lifestyle of each and every American. He’s published extensively about the flows of copper, accessible here. So where do we find copper in an industrial building? By far, most is found in wiring and plumbing, but we also find copper in central air conditioning systems, elevators, conveyor belts, and architectural elements like roofing and gutters. Any equipment that’s left in an industrial building will also have a small amount of copper, as will any electronics. Copper is one of the first things to be removed from a building before it’s demolished. We typically call in a specialty metals recycler to come and perform this removal, and they will usually provide a quote of what they’ll pay for the copper they are able to recover. As the building is demolished, any remaining copper will be separated and set aside for recycling. I was surprised to learn that there are still a number of facilities in the U.S. who recycle copper, using a variety of techniques to process the materials and then smelting them (heating them to a high temperature) to remove impurities. Like aluminum, copper is very easily recycled without compromising its quality. The facilities that do this are quite complicated, use large amounts of water and energy, and tend to have highly regulated waste management, wastewater, and air permits. The graph below, from the International Copper Study Group, shows our hunger for copper to support all kinds of development activities, and the degree to which secondary (recycled) copper is an important source. While U.S. facilities continue to produce copper for the international market, a large amount of both primary and secondary copper production has shifted to Asia. Is this because environmental requirements are less of a burden there? Or because labor is cheaper? I tend to think it’s a combination of those factors combined with the fact that much of the demand for copper now resides in Asia, where so much primary industrial production is now focused. I’m constantly having to remind myself of the progression of training and certification required in California to do any kind of consulting related to asbestos, so I thought I’d capture it in a blog post.

The regulations for asbestos consultants are found in Title 8 of the California Code of Regulations, Section 341.15. They are based on federal AHERA requirements are found in Title 40 of the Code of Federal Regulations, Part 763, Subpart E, Appedix C. The federal training and certification program includes:

In order to be certified to consult about asbestos issues in California, there is a progression of training and experience: Step 1: Federal AHERA inspector training. Requires three day course and passing a test. Once you become a building inspector, you can conduct asbestos inspections and collect samples, but you must work under the supervision of a Certified Asbestos Consultant. Step 2: Federal AHERA Abatement Contractor/Supervisor training. Five more days of training is required, focusing on the practicalities of doing abatement work. Step 3: Six months of supervised experience under the direction of a certified asbestos consultant. Step 4: California Site Surveillance Technician exam and registration. An application is submitted, the exam taken, and then you’re certified to perform site inspection independently. Step 5. Federal AHERA Management/Planner training. Two more days of training on how to prepare operations and maintenance programs and plan for abatement projects. Step 6. Federal AHERA Project Designer training prepares you for responding to incidents involving releases of asbestos fibers, conducting abatement projects in schools and public buildings, and understanding in detail the health risk aspects of asbestos abatement. Step 7. Additional year of experience. Step 8. California Asbestos Consultant exam and registration. Another application is submitted to document and verify all your credentials and experience, and once you pass the exam you’re certified to perform all aspects of asbestos management and planning. The state issues official ID cards for each certification. The certifications are good for one year, and must be renewed annually after completing 3 days of refresher training. |

Marty WaltersEnvironmental Scientist Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed