|

Financial industry smarts for environmental professionals No 2 in a meandering series I had a chance to work on some reviews this past week for both ground leases and sale-leasebacks, so I thought it would be fun to talk about how these affect the way that environmental due diligence is performed and decisions are made about environmental risks.

Before I get into ground leases and sale-leasebacks, let’s make sure everyone is clear about the definition of the collateral that is securing a loan or lease or other credit being extended. In addition to real property - land and buildings - the collateral can include a ground lease, equipment, and the value of contracts. (By the way, when you hear the term “boot collateral,” that usually refers to real estate or other property that is included in the loan but does not contribute value to the security package.) Ground Lease A ground lease means that the ownership of the underlying land is different from the buildings or factory placed on the land. Most ground leases have very long terms such as 50 or 99 years. In the U.S., at the end of the lease term the improvements on the land typically revert back to the lessor. However, in some countries such as Japan the lease term tends to be a little shorter and all improvements must be removed at the end of the lease term. Whenever possible, I try to review the ground lease before I do any due diligence on a loan with this feature. That way, I can review any disclosures made by the ground lessor, any indemnities being made or required, and any terms and conditions required at the end of lease term or in the event of transfer. Our legal team ensures that the terms of the lease agreement are acceptable to the bank in the event that there’s a default on the loan and the bank considers taking title to the asset. Understanding the ground lease can help determine the scope of the environmental assessment, for example:

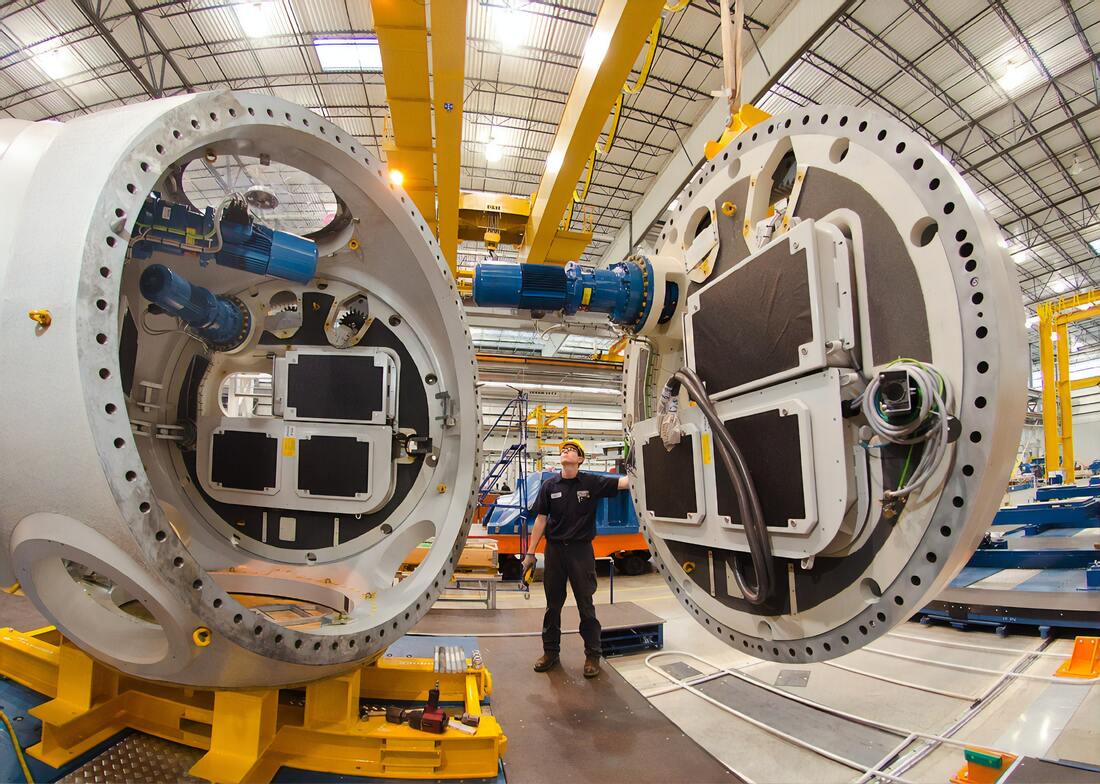

Sale-Leaseback A sale-leaseback transaction involves a simultaneous sale of the property with a lease of the property back to the seller. The property could be real estate, but it could also be equipment or other assets with sufficient value to serve as security, everything from airplanes to forklifts to conveyer belts. I’ve even worked on transactions involving the sale-leaseback of every piece of equipment in a factory. Why would a company want to enter into a sale-leaseback type of financing, given the complexities and tax issues involved?

From an environmental standpoint, there is one key consideration for sale-leaseback transactions. Rather than being a lender, the bank becomes the owner of the property or equipment, so any due diligence needs to be scoped to identify risks that would affect a property owner. In the United States, the bank no longer benefits from the secured creditor provisions in the federal Superfund law or state cleanup laws. In addition, the bank could become jointly liable for environmental compliance under the federal hazardous waste law, the Resource Conservation and Recovery Act, and state counterparts.

Any due diligence for a sale-leaseback needs to consider not just contamination at the property, but also other conditions or operations at the property that could result in an owner obligation or liability. Once the due diligence gets reviewed by the technical experts, a consultation may be needed with legal counsel to ensure that both the purchase agreement and the lease agreement reflect the true conditions at the property and include provisions that protect the bank from environmental liability. There are some kinds of businesses that are simply not good candidates for this kind of transaction, including those with intensive chemical use like plating shops and hazardous waste management companies. Photo credit: Science in HD on Unsplash Views and opinions expressed on my blog are mine alone and have not been reviewed or approved by my employer. Any errors in my blog posts are entirely my own.

1 Comment

I got an early education about how different legal systems can shape decision making and problem solving. I grew up in Hawai’i during a time when there was a growing awareness of Hawaiian arts, language, culture, and science. And along with that came an examination of the legal systems put in place during the monarchy that grew from the concept of shared responsibility for land resources. Because the monarchy was illegally overthrown by Americans, its laws and land system have never fully disappeared from the legal landscape, and some of those concepts still exist today.

The story of Facebook CEO Mark Zuckerberg’s efforts to create a remote and exclusive estate on Kauai ran afoul of legal and constitutional rights of native Hawaiians, his involvement being only a part of a really interesting saga Trisha Kehaulani Watson wrote for Honolulu Civil Beat in 2019. Whether you are financing the development of an estate in Hawai’i, signing an equipment lease in South Korea, or foreclosing on contaminated land in New South Wales, Australia, it’s critical to understand how the laws in your jurisdiction affects your environmental risks. Not only do you need to understand the environmental laws of the place where you are doing business, but you need to then match your understanding of environmental risks to the options available to financiers to collect a loan balance, enforce on property, or exit a contract. The way that different jurisdictions regulate environmental impacts can have a big impact on whether a condition triggers action to address a health or safety condition under a particular law or regulation. California’s very specific and detailed requirements for soil vapor intrusion means that many more properties in California are being cleaned up for chlorinated solvents in soil gas compared to Texas, where there are no specific requirements. The differences between different states can extend to lender protections. For example, in California, lenders have broad rights to investigate and even clean up properties without taking on legal liabilities under state cleanup laws, even where the lender takes title to the property for the purpose of recovering loan exposures, as long as the property is then disposed of promptly, usually within a year. But in some states these protections may not extend to affiliated legal entities that are formed to hold the asset. Lender protections that are written into the U.S. Superfund law and many U.S. state cleanup laws will not apply to other kinds of environmental requirements, for example underground storage tanks or asbestos in building materials. Once again, it’s critical to understand the jurisdiction you’re working in and to get the right kind of legal support to sort out how jurisdictional requirements match to the environmental risks identified for a particular financial transaction. And then there’s the difference between civil law and common law countries and how that relates to tort liabilities….ah, but that’s a topic for another day. |

Marty WaltersEnvironmental Scientist Archives

March 2021

Categories

All

|

Proudly powered by Weebly

RSS Feed

RSS Feed